IMPORTANT NOTE: This article is based on the archaic article in the Archaeological Survey of India reports from 1873-75. It calls the yoginis “female demons.” As reader Venkat Veeraraghavan noted, “The Yoginis are not Female Demons but Female Goddesses who each serve one of the Mahavidyas. The 64 Yoginis represent the sum total of energy in the Universe.”

Devata.org also recognizes these female entities as “goddesses,” and does not agree with the negative implications of the term “demon” used in the original report.

The Chaunsat Yogini Temple of Bheraghat Jabalpur enshrines 64 yoginis and 15 other female goddesses. Shiva and Ganesha are the only two male gods.

The temple and its possible relevance in relation to Angkor Wat are discussed in this article.

See this related article with detailed photos (updated in 2012): “The 81 Yoginis of Bhedhaghat” by Divya Deswal

Photographer Sudhansu Nayak has posted another visual article here: “64 Yogini Temple, Hirapur – A detailed view inside“

See this article translated into the Tamil language by Santhipriya here:

![1875-yoginis-55-58 Gauri sankara yoginis 55 58 Chausath Yogini Temple Complete Inventory of Goddesses and Gods]()

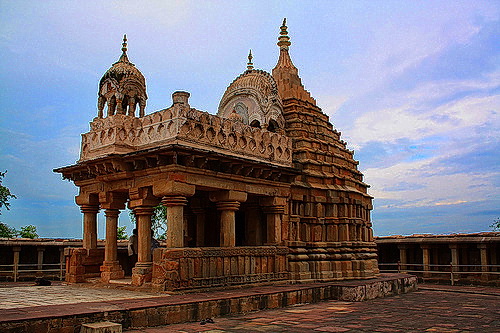

The yogini temple of Bheraghat Jabalpur, circa 1875.

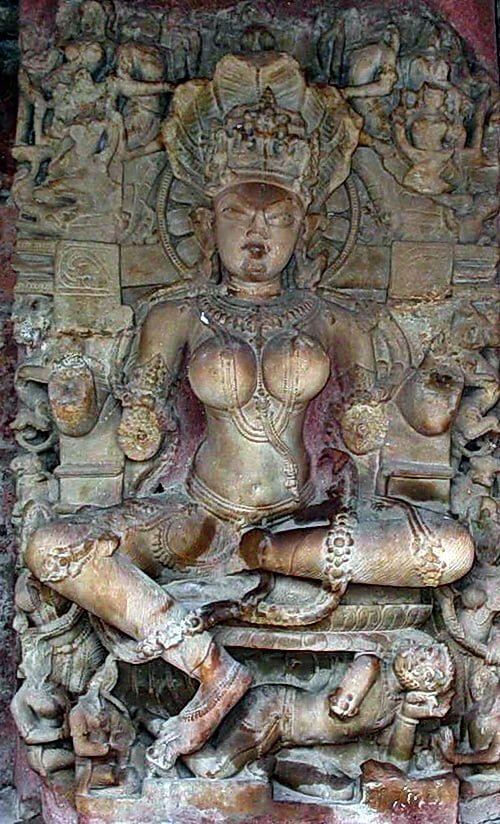

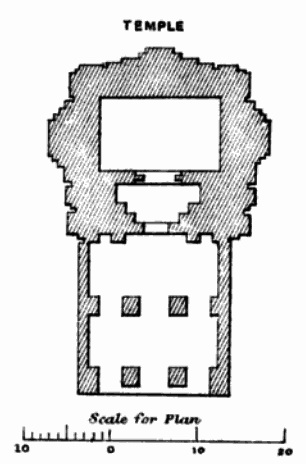

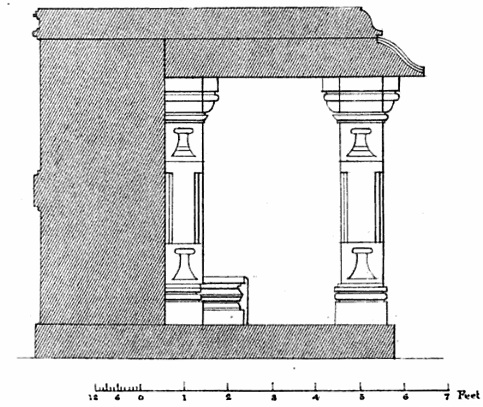

The cloister’s inner diameter is 116 feet 2 inches, and the outer diameter 130 feet 9 inches. This ring is divided into a circular row with 84 square pillars so that each cloister is only 4 feet 9 inches wide and 5 feet 3 1/2 inches high under the eaves.

Using 84 pillars, the cloister is divided into as many spaces. Three niches—two to the west, and the other to the south-east—remain open as entrances. The remaining 81 spaces are fitted with pedestals between the pilasters for the statues.

![Bheraghat-yogini-temple-site-plan Gauri sankara site plan Chausath Yogini Temple Complete Inventory of Goddesses and Gods]()

Site plan showing the 84 cloisters of the yogini temple at Bheraghat.

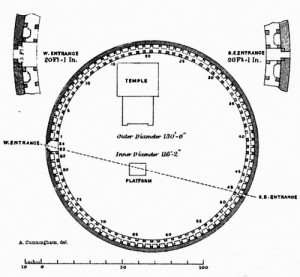

Among the statues two poses are seen: sitting and standing. Most are four-armed goddesses who are especially remarkable for their breast size. Most images are yoginis (Sanskrit), or female demons who serve Durga. The temple is, therefore, commonly known as the Chaunsat Yogini, or “sixty-four yoginis.”

Eight figures are identified as ashta sakti, or female energies of the gods. Three seem to be personified rivers. All the sitting figures are taken to be yoginis. Each one is highly ornamented and made of a grey sandstone.

Four dancing female figures are not inscribed (Nos. 39,44, 60 and 78]. These are made of a purplish sandstone and are much less ornamented. One of them, No. 44, is thought to be the goddess Kali. The others seem to be other forms of that deity.

Siva and Ganesha [Nos. 15 and 1] are the only two male figures.

NOTE: The inventory below is based on the Archaeological Survey of India reports from 1873-75. Unfortunately, modern photos of the site show variations to the names and numbering system originally cited. Please contact me (kentdavis@gmail.com) if you can help clarify these discrepancies.

Complete detailed inventory of the Chausath yogini temple goddesses and gods:

1. Sri Ganesha — Sitting god.

2. Sri Chhattra Samvara — A Sambar deer, with deer decorating this seated yogini’s pedestal. The allusion to chhattra is not understood..

3. Sri Ajita — This seated goddess is the feminine form of Ajita-Siva, “the unconquered” with a fabulous lion as her symbol.

4. Sri Chandika — Durga-Maheswari, “ the furious,” featuring skeletons and a prostrate man. A standing sakti goddess who is known as one of the “eight powers of Durga.”

5. Sri Mananda — Probably named for Ananda, the happy, or joyful. The symbol with this seated yogini is the lotus.

6. Sri Kamadi — The seated feminine form of Kamada, the fabulous cow of plenty that sprang from the Sea of Milk. Kamadi is therefore the goddess who grants all desires; her symbol of the yoni suggests that the desires are sexual. Two males are worshipping her.

7. Sri Brahmani —The goose on the pedestal indicates that this goddess is the sakti, or female energy, of Brahma.

8. Sri Maheswari —The bull Nandi on the pedestal shows that this goddess is the sakti, or female energy, of Maheswara, or Siva.

9. Sri Tankari — Probably derived from tanka, a sword or axe, both weapons which are carried in two of the ten hands of this yogini. Her symbol is a fabulous lion.

10. Sri Jayani — The “conquering” goddess is featured seated. Her symbol is a feline.

11. Sri Padma-hansa — This seated goddess is not known. Her symbol is flowers.

12. Sri Ranajira — Seated goddess of the “battle field” symbolized with an elephant.

13. Name lost — This seated goddess is symbolized by “Nagni” (?).

14. Sri Hansini , or Hansinira. — Unknown seated goddess with the symbol of the goose.

15. Not inscribed — A 16 armed 3-eyed Siva (male).

16. Sri Iswari — This seated yogini represents sakti, or female energy, either Durga or Lakshmi.

17. Sri Thani — The immovable goddesss. Sthanu is a name of Siva meaning “firm” or “immovable.” Derived from stha to stay, or sthd to stand still. Her appropriate symbol is the mountain peak.

18. Sri Indrajali — She is a seated “deceiving” goddess. Her elephant symbol suggests the name of Indra, with perhaps an allusion to his well-known deceits.

19. Broken — A seated yogini with a bull and skeletons among her symbols.

20. Statue missing.

21. Sri Thakini — Unknown seated goddess, however due to the camel symbol on her pedestal, linguists suggest Ushtrakini, or the cameline goddess.

22. Sri Dhanendri —Dhan means to “sound” but it is spelt with the dental dh. The name may simply mean the “sounding goddess.” She is depicted seated with a prostrate man worshipping her.

23. Statue missing.

24. Sri Uttala may mean the “swift goddess,” as implied by the antelope symbol. She is seated.

25. Sri Lampata — The “courtesan goddess” depicted seated with a prostrate male worshipper.

26. Sri Uha — This seated goddess may be the personification of the Saraswati River. Yogini 29 and 68 personify the Ganges and Jumna. The name may be derived from Uha, “to reason” meaning the “reasoning goddess” — an appropriate name for Saraswati, the goddess of speech and eloquence. This theory is supported by the peacock on her pedestal, which is the symbol of the Saraswati river.

27. Sri *tsamada — Seated goddess with a boar on her pedestal. The initial letter unknown.

28. Sri Gandhari — A winged goddess, with the symbol of a horse or ass. The name may be connected with gandharvva, “a horse,” associated with swiftness, which is also implied by her wings.

29. Sri Jahnavi —This is a well-known name of the Ganges; and as her symbol is a makara, or “crocodile,” it is certain that this is the river goddess herself.

30. Sri Dakini —This seated yogini is characterized by the Hindi term, dakin, the common name for a witch or she-demon. She has the symbols of a man and a skeleton.

31. Sri Bandhani — This seated goddess’s name is derived from bandh, to bind, or bandhan, hurting, injuring, killing. Historians suggest that the man on the pedestal may be a prisoner.

32. Sri Darppahari — Probably a mistake for Darbbahari. Darbba means a rakshasa, or demon, from dri, to “tear;” and darbbahari would be the “tearer,” — a title confirmed by the lion on the pedestal, and by the seated goddess’s lion head.

33. Sri Vaishnavi is the name of the sakti, or personified energy of Vishnu. She is seated on Vishnu’s mount garuda on the pedestal.

34. Sri Danggini — First letter doubtful. A seated yogini also featuring garuda.

35. Sri Rikshini — A crocodile is featured on the pedestal of this yogini. The value of the first letter is uncertain (see No. 27). The symbol of the crocodile seems to point to a river goddess; and Rikshini would be the name of the Narbada, which rises in the Riksha mountain. A female figure at Tewar, standing on a crocodile, is called Narbada mai, or “Mother Narbada.”

36. Sri Sakini — Wilson describes sakini as “a female divinity of an inferior character, attendant equally on Siva and Durga.” Others remark that “in the Baital Pachisi sakinis are mentioned in connection with cemeteries.” They are, in fact, the female goblins whom Raja Vikram saw eating the dead bodies. The symbol of a vulture on the pedestal of this seated goddess is, therefore, appropriate.

37. Sri Ghantali — The “bell” yogini, with a bell or ghanta on her pedestal.

38. Sri Tattari — The name implies a kettle-drum, or any musical instrument. We presume that name refers to the “trumpet,”’ as the seated goddess has an elephant’s head, and there is an elephant on the pedestal. Tatta is the imitative sound of the trumpet, like tantarara in English.

39. Not inscribed — A dancing female.

40. Sri Ganggini — The first letter is doubtful. The symbol seen is a bull.

41. Sri Bhishani — The “terrific goddess”…as in “terror” is seated with a rayed headdress. Bhishana is a name of Siva.

42. Sri Satanu Sambara —Sambara refers to the Sambar deer, which is also seen on the pedestal of this seated goddess.

43. Sri Gahani — Ram on pedestal of this seated goddess. The first letter is doubtful. The name may mean the destroying goddess, from gah, to destroy.

44. Not inscribed — A dancing female in the style of Kali.

45. Sri Duduri — The derivation is not clear: du means “bad,” and also “to give pain.” Perhaps it is only a duplication of dur = pain, which would imply the “pain-giving” yogini. The symbol of the saddled horse remains puzzling on this seated yogini.

46. Sri Varahi — One of the saktis of Vishnu, as the Varaha Avatara. There is a boar on the pedestal, and this seated sakti goddess has a boar’s head.

Note: Reader Venkat Veeraghavan comments: “Varahi in this case is not the female SHakti of the Varaha Avatar of Vishnu. Varahi is a pig-faced goddess who is one of the Upadevis (Minor Goddess) associated with Shodashi or Shrividya one of the 10 Mahavidyas.”

47. Sri Nalini—perhaps from nal, “to bind.” There is a bull and cow on the pedestal, and the seated yogini has a cow’s head.

48. SE Entrance

49. Statue missing.

50. Sri Nandini is the title of this seated goddess Parvati. The lion on the pedestal implies that Nadini, or “roarer” may be her true name.

51. Sri Indrani —As there is no Aindri in this collection, this seated goddess Indrani must be intended as the sakti, or female energy, of Indra.

52. Sri Eruri, or Ejari — The first reading seems preferable. The yogini has a cow’s head, and there is a cow on her pedestal.

53. Sri Shandimi — Shanda means a bull; but the animal on the pedestal of this broken figure appears to be a donkey.

54. Sri Ainggini — An elephant-headed goddess, with an elephant-headed man on her pedestal. The name seems to refer to ingga, “movable,” which is itself derived from igi, “to go.”

55. Name lost — A seated goddess with a boar’s head and a boar on her pedestal.

56. Sri Teranta, or perhaps Techanta — This 20-armed seated goddess has a figure of Mahesasura on her pedestal, so her title must relate to a name of Durga, who is also called Mahishasuramardini (mardini = killer, fem.), the destroyer of Mahishasura.

57. Sri Paravi — Perhaps a mistake for Parvati, as the seated goddess has 10 arms, which point to Durga.

58. Sri Vayuvena — This broken figure’s name means “Swift as the wind.” The antelope on the pedestal may allude to her swiftness.

59. Sri Ubhera Varddhani — “The increaser of light” is the name of this broken goddess image. There is a class of 64 demi-gods named abhaswaras who, from their number, appear to have a connection with the 64 yoginis. The bird on the pedestal gives no assistance towards the meaning of the name.

60. Not inscribed — A dancing female with an elephant symbol on her pedestal.

61. Sri Sarvvato-mukhi — This goddess has 12 arms and 3 heads, with a head also between her breasts. The number of heads explain the name of “Facing everywhere.” Her pedestal displays the leaves of the lotus and six points of a double triangle which may allude to her name.

62. Sri Mandodari — The name of this broken yogini means “slow-belly.” Sri Mandodari was also the name of the daughter of King Mayasura of the Danavas and the celestial dancer Hema. Mandodari was a pious woman who feared nothing but unrighteousness and lies. Her beauty and appeal led her to become the first, and favorite, wife of Ravana, the Lord of Lanka. On her pedestal two men worship her with folded hands.

NOTE: Reader Ventkat Veeraraghavan comments: “Mandodhari= Manda + Udari In this case Manda does not mean slow….it means depressed and Udara is belly; hence the dual compound translates to: “One with a depressed navel/belly region aka a thin waisted lady.”

63. Sri Khemukhi — The long-beaked bird on the pedestal seems to refer to the name, which may perhaps be translated “voracious mouth”” from khed, to eat. Her statue is broken.

64. Sri Jambavi — The “bear goddess,” with a bear on her pedestal, evidently points to Jambavat, the fabulous king of the bears who was the father-in-law of Krishna. This statue probably had a bear’s head; but it is now broken.

65. Sri Auraga — The first letter is not certain, and the statue is broken. A naked man on the pedestal does not offer any more clues about this figure.

66. Statue Missing.

67. Sri Thira-chitta — Probably intended for Sthira-chitta, “the firm or steady minded.” This seated goddess shows a man praying with folded hands on her pedestal.

68. Sri Yamuna — This seated goddess is the river Jumna personified. The tortoise on the pedestal was her symbol.

69. Statue Missing.

70. Sri Vibhasa — Either connected either with vibheshu, “terrible,” or with vibhitsu, “the piercer.” The skeleton and prostrate man on the pedestal suggest an appellation of Durga.

71. Sri Sinha-sinha — This lion-headed goddess, with the lion headed-man on her pedestal, is probably intended for Narasinha, the sakti or female energy of the Narasinha avatara.

72. Sri Niladambara — Probably the same as Nilambara, a female demon. The garuda on this yogini’s pedestal established her connection with Vishnu.

73. Statue worn away — A flame is still seen on the pedestal of this seated goddess.

74. Sri Antakari — A seated goddess, with open mouth, ready to devour — must mean the “death-causer,” from anta, “end or death.” Antaka is a name of Yama, the god of death; but the bull on the pedestal seems to refer to Siva, who, as Pasupati, is also the god of death and destruction.

75. Name lost — This seated goddess displays a long-nosed bull on her pedestal.

76. Sri Pingala — This seated goddess’s name means “tawny, or brownish-red.” The peacock on the pedestal points to Eaumari, the sakti of Skanda Kumara or Karttikeya.

77. Sri Ahkhala — On the pedestal two men with folded hands worship this seated sakti goddess. The reading of the name is clear but the meaning is unknown.

78. Not inscribed — A dancing yogini with a bird pictured on her base.

79. Sri Kshattra-dharmmini — The compound kshattradharmma means the duty of a kshattra, or soldier, i.e. bravery. But as kshattra is derived from kshad, “to eat, to rend, to tear to pieces,” the title of this goddess would mean the “tearer to pieces, or the devourer.” The image shows seated females with skulls in head-dresses. A bull with a chain appears on her pedestal.

80. Sri Virendri — Another images with seated females armed with sword and shield. The pedestal has a horse’s head and skeletons. Perhaps the name should be Vairendri, the “inimical goddess,” rather than Virendri, the “heroic goddess.”

81. Statue missing.

82. Sri Ridhali Devi — The seated “hurtful goddess,” from rih, to “hurt.” The animal, with claws, on the pedestal seems to confirm this derivation.

83-84 – West Entrance.

The result of this examination shows that the statue set up in this circular cloister may be divided into five distinct groups as follows:

Saktis, also called ashta-sakti……………………..8 statues

Rivers: Ganges, Jumna, and Saraswati…………3

Dancing goddesses: Kali, etc………………………4

Gods: Siva and Ganesha…………………………..2

Yoginis (chaunsat yogini) 57 intact, 7 lost……….64

Total……………………………………………………..81

Two entrances [= 3 spaces]…………………………3

Total……………………………………………………..84

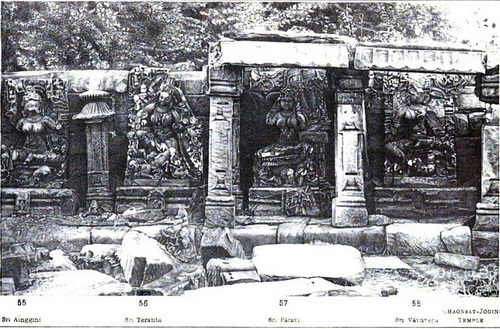

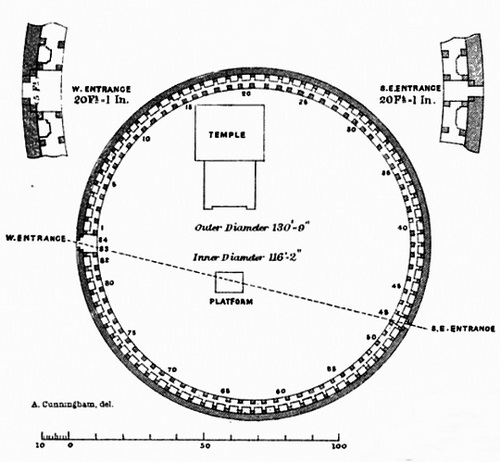

![yogini-statue-inscriptions Gauri sankara inscriptions Chausath Yogini Temple Complete Inventory of Goddesses and Gods]()

Yogini statue inscriptions.

The post Chausath Yogini Temple – Complete Inventory of Goddesses and Gods appeared first on Angkor Wat Apsara & Devata: Khmer Women in Divine Context.